When the Earth Shakes, the Ocean Suffers:

How Deep-Sea Earthquakes May Trigger Methane Leaks—and a Cascade of Marine Life Loss

Earthquakes are usually thought of as land-based disasters—cracked roads, collapsed buildings, and shaken cities. But some of the most profound consequences of seismic activity may be happening far from our sight, deep beneath the ocean floor.

Growing evidence suggests that undersea earthquakes can trigger methane releases, which can kill marine life in the deep ocean AND then fuel bacterial explosions that disrupt fragile marine ecosystems. This chain reaction—beginning with tectonic movement and ending with biological collapse—may help explain recent, troubling patterns in marine die-offs along the world’s coastlines.

Step One: Earthquakes and the Release of Buried Methane

Methane Leaks

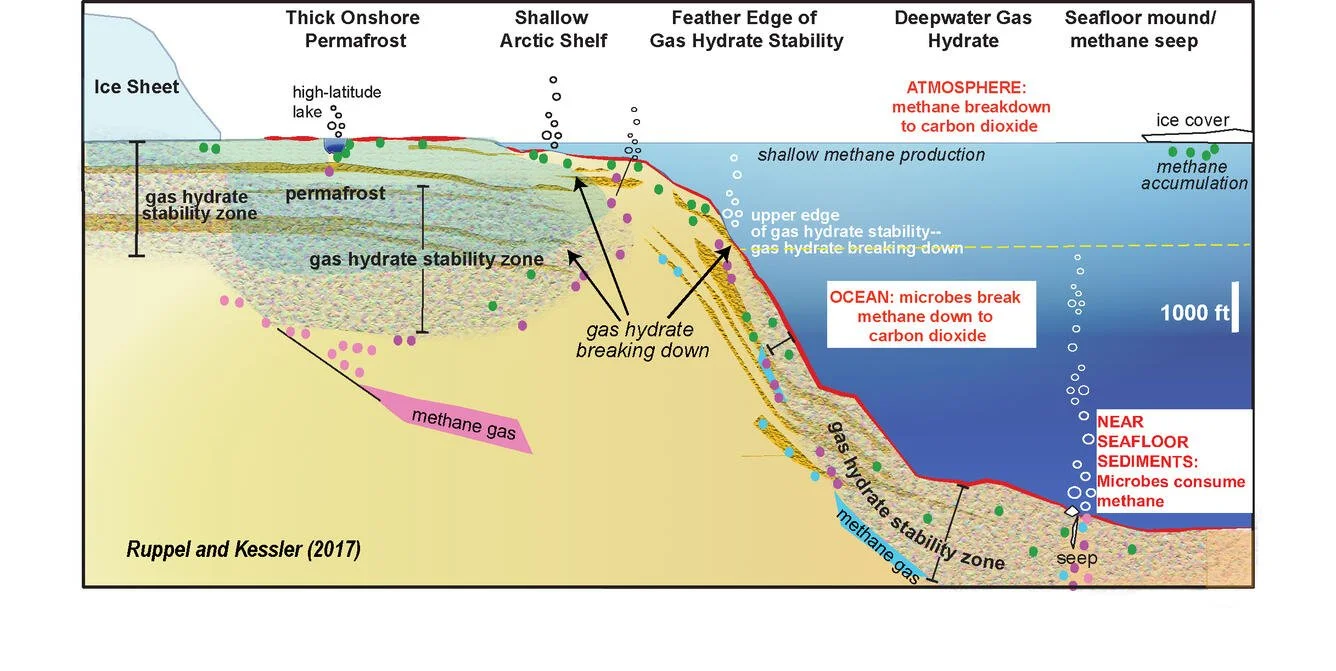

Methane is stored throughout the Earth’s crust, often trapped beneath sediments or locked into methane hydrates which are ice-like structures common along continental shelves and deep-sea fault zones. These reservoirs are normally stable. But earthquakes change that.

Research summarized by Climate Central and other scientific groups shows that seismic shaking can fracture seabed sediments, opening pathways for methane to escape into the water column. One striking historical example occurred during a 1945 earthquake in the Arabian Sea, where researchers believe massive methane releases followed violent seabed disturbance.

More recently, offshore Italy, fishermen in 2017 reported a 30-foot jet of discolored water erupting from the sea near Montecristo. Geologists later identified a chain of mud volcanoes, actively bubbling methane into the surrounding waters. Similar methane bubble plumes have been documented worldwide, including along the U.S. West Coast.

Even coastal communities are affected. In Southern California, methane seepage linked to geological activity has led to home evacuations in places like Newport Beach, reminding us that these processes are not confined to the abyss.

Step Two: Methane Feeds a Hidden Army—Methanotrophic Bacteria

Methane does not simply vanish once it enters the ocean. Instead, it becomes fuel.

Certain microbes—called methanotrophs—consume methane as their sole source of carbon and energy. These bacteria use an enzyme known as methane monooxygenase to oxidize methane, converting it into biomass and carbon dioxide. They thrive in environments rich in methane: soils, landfills, wetlands—and critically—deep-sea sediments and fissures.

Under normal conditions, methanotrophs play a vital role, acting as a biological filter that prevents methane from reaching the atmosphere. But when methane release increases suddenly—as it can after seismic events—bacterial populations can explode.

This is where the cascade begins to accelerate.

Step Three: When Bacterial Blooms Become Ecological Stressors

A surge in methane-eating bacteria can profoundly alter local ocean chemistry:

Oxygen depletion as bacteria consume oxygen during methane oxidation

Shifts in microbial balance, favoring opportunistic or pathogenic species

Changes in sediment chemistry, affecting bottom-dwelling organisms

In deep-ocean environments—where ecosystems are already finely balanced—these changes can ripple outward. Animals adapted to stable conditions may suddenly face hypoxia, altered food webs, or exposure to unfamiliar microbes.

Step Four: Marine Life at Risk—From the Deep Sea to the Coast

Along California’s Central Coast, hundreds of marine mammals have stranded or fallen ill, coinciding with toxic algal blooms, bacterial infections, and food-chain disruptions. While no single factor explains these events, the convergence of stressors is alarming.

One particularly striking example involves sea star wasting disease, a condition that has devastated sea star populations across the Pacific. Recent reporting suggests that a previously unidentified pathogen may be responsible—but the broader question remains: what environmental conditions allowed this pathogen to thrive?